เรื่องพื้นฐาน

ดันเจียนแอนด์ดราก้อนเป็นเกมที่คุณและเพื่อนจะได้สวมบทบาทและเล่าเรื่องราวร่วมกัน ขณะที่ข้อมูลส่วนที่แล้วนั้นสอนคุณว่าเล่นเกมนี้อย่างไร และสร้างตัวละครที่คุณจะเป็นฮีโร่ของเรื่องราวได้อย่างไร ส่วนต่อไปนี้จะเป็นข้อมูลสำหรับผู้เล่นพิเศษที่จะคอยเป็นผู้ดำเนินเกมและทำให้แน่ใจว่าทุกคนจะสนุก ผู้เล่นคนนี้คือ ดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master) หรือดีเอ็ม (DM) การเป็นดันเจียนมาสเตอร์นั้นสนุก เป็นผู้มีอำนาจตัดสินใจ และเป็นประสบการณ์ที่ถือว่าเป็นรางวัลในการเล่น และในบทนี้เราจะมาทำความเข้าใจถึงเรื่องพื้นฐานการเป็น DM กัน

DM ทำอะไร?

DM จะเล่นเป็นหลายบทบาทที่สนุกสนาน:

เป็นนักแสดง DM จะเล่นเป็นมอนสเตอร์ เป็นคนเลือกแอ็คชันและทอยลูกเต๋าในการโจมตี DM ยังเล่นเป็นผู้คนทั้งหมดที่ตัวละครฝั่งผู้เล่นจะได้พบเจอ

เป็นผู้กำกับ เหมือนกับผู้กำกับในภาพยนต์ DM จะเป็นผู้ตัดสินใจ (และอธิบาย) ว่าตัวละครของผู้เล่นจะเจอกับการผจญภัยแบบใด DM ยังรับผิดชอบความเร็วในการเล่นแต่ละครั้งการเล่นหรือเซสชันและสร้างสถานการณ์ที่เล่นได้อย่างสนุกสนาน

เป็นนักด้นสด เป็นงานหลักของ DM เลยที่จะต้องตัดสินใจว่าจะใช้กฏอย่างไรขณะดำเนินเกม และต้องจินตนาการถึงการกระทำของผู้เล่นที่จะตอบสนองต่อสิ่งนั้น และต้องทำให้เกมสนุกสำหรับทุกคนด้วย

เป็นกรรมการ เมื่อเกิดความคลุมเครือว่าควรจะไปต่อทางไหน DM จะเป็นผู้ตัดสินว่าจะใช้กฏอย่างไรให้เหมาะกับสถานการณ์

เป็นนักเล่าเรื่อง DM จะสร้างการผจญภัย กำหนดสถานการณ์ที่เกิดขึ้นตรงหน้าของผู้เล่นเพื่อให้พวกเขาได้ออกสำรวจและมีปฏิสัมพันธ์กับโลกของเกม

เป็นครู บ่อยครั้งที่งานของ DM เป็นการสอนผู้เล่นใหม่ว่าเกมนี้เล่นอย่างไร

เป็นผู้สร้างโลกของเกม DM จะสร้างโลกที่การผจญภัยของผู้เล่นเกิดขึ้น แม้ว่าจะใช้เซ็ตติงที่ตีพิมพ์ขาย คุณก็ยังต้องสร้างบางส่วนด้วยตัวคุณเอง

เคล็ดลับสำหรับ DM

สิ่งที่สำคัญที่สุดของการเป็น DM ที่ดีคือการจัดการให้ทุกคนสนุกในการเล่นเกม เคล็ดลับเหล่านี้จะทำให้สิ่งต่าง ๆ ราบลื่นขึ้น

ยอมรับการเล่าเรื่องร่วมกัน D&D เป็นการเล่าเรื่องราวกันเป็นกลุ่ม ดังนั้นต้องให้ผู้เล่นคนอื่น ๆ ได้ร่วมมือผ่านถ้อยคำและวีรกรรมจากตัวละครของพวกเขา ส่งเสริมให้ผู้เล่นได้มีส่วนร่วมโดยการถามว่าตัวละครของพวกเขาทำอะไร

มันไม่ใช่การแข่งขัน DM ไม่ได้แข่งขันอะไรกับผู้เล่นอื่น มันเป็นงานของคุณที่จะสร้างความท้าทายที่สนุกสนานและทำให้เรื่องราวดำเนินไป

มีความยุติธรรมและยืดหยุ่น ปฏิบัติต่อผู้เล่นของคุณอย่างยุติธรรมและเป็นกลาง กฏเกมจะช่วยคุณในเรื่องนี้ แต่เมื่อคุณต้องทำหน้าที่เป็นกรรมการ พยายามตัดสินใจโดยยึดเอาความสนุกของผู้เล่นเป็นสำคัญ

สื่อสารกับผู้เล่นของคุณเสมอ การสื่อสารอย่างเปิดเผยเป็นหลักสำคัญที่จะเล่น D&D ได้อย่างดีที่สุด ปัญหาหลายอย่างสามารถแก้ไขได้หรือแม้แต่ป้องกันได้ด้วยการพูดคุยอย่างเปิดเผย ถามคำถามและขอคำติชมภายหลังหรือระหว่างเซสชัน

มันไม่เป็นไรเลยหากจะทำผิดพลาดบ้าง ถ้าคุณมองข้ามหรือทำอะไรผิดไป เพียงแก้ไขและดำเนินเกมต่อไป ไม่มีใครคาดหวังให้คุณจำได้ทุกกฏหรือทุกรายละเอียด แม้ว่าคุณจะไม่รู้สึกถึงความผิดพลาดไปจนเล่นจบเซสชันแล้ว มันก็ไม่เป็นไรเลยที่จะระบุความผิดพลาดและมาแก้ไขกันในช่วงก่อนเล่นเซสชันถัดไป

สิ่งที่คุณต้องมี

สิ่งที่คุณต้องมีในการเริ่มเล่นไม่ได้เปลี่ยนไปมากเลยตั้งแต่เกมนี้ออกขายตั้งแต่ปี 1974

ดันเจียนมาสเตอร์หนึ่งคน

ผู้เล่นหนึ่งคนจะทำหน้าที่พิเศษโดยการเป็นดันเจียนมาสเตอร์

บางคนรักที่จะเป็น DM ขณะที่บางคนก็จบลงที่รู้สึกติดกับดักว่าเป็น “DM ตลอดกาล” สำหรับกลุ่มเล่นเกมของตัวเอง ข้อมูลในบท “ขนาดกลุ่มเล่นเกม (Group Size)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) มีคำแนะนำถึงความเป็นไปได้ที่ผู้เล่นทุกคนจะผลัดกันเป็นดันเจียนมาสเตอร์

กลุ่มผู้เล่น

ผู้เล่นที่ไม่ได้เป็นดันเจียนมาสเตอร์จะรับบทเป็นฮีโร่ เรียกอีกอย่างคือเป็นตัวละคร (character) หรือเป็นนักผจญภัย (adventurer)

D&D จะเล่นได้อย่างสนุกด้วยผู้เล่น 4-6 คนไม่รวม DM แต่ก็เป็นไปได้ที่จะรันเกมด้วยนักผจญภัยที่น้อยกว่าหรือมากกว่านี้ ดู “ขนาดกลุ่มเล่นเกม (Group Size)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) สำหรับคำแนะนำในการเล่น

หาคนมาเล่นด้วย

จะหาผู้เล่นจากที่ไหนล่ะ? นี่เป็นคำแนะนำว่าจะหาจากที่ไหน:

- ร้านเกมหรือร้านขายของงานอดิเรก (มีระบบรายการร้านในเว็บไซต์ Wizards of the Coast ที่สามารถช่วยคุณได้ในการหาร้านที่อยู่ใกล้คุณที่มีบริการเล่น D&D)

- เหล่าเพื่อน ๆ, ครอบครัว, คนในชุมชน, และเพื่อนร่วมงานที่ชอบเล่นเกมหรือเรื่องราวแฟนตาซี

- ชมรมเล่นเกมที่โรงเรียน

- โซเชียลมีเดียและเว็บพูดคุยออนไลน์

- งานชุมนุมเกมต่าง ๆ

สถานที่เล่นเกม

พื้นที่น้อยที่สุดที่คุณต้องการในการเล่น D&D คือห้องที่ทุกคนในกลุ่มสามารถนั่งได้สบายในการเล่น

เมื่อคุณเลือกสถานที่ที่จะเล่น ให้สอบถามผู้เล่นถึงขอบเขต (limit) ต่าง ๆ ของพวกเขา ผู้เล่นบางคนมีปัญหากับที่แสงน้อย, เพลงที่เปิดเบื้องหลัง, กลิ่นฉุน, พื้นที่แคบ, หรือมีอาการแพ้เฉพาะอย่าง พยายามจัดหาสิ่งที่คุณทำได้และบอกกล่าวกันถึงสิ่งที่คุณหาไม่ได้ก่อนที่จะเริ่มวางแผนการเล่น

ถ้าเป็นไปได้ ควรเล่นเกมในพื้นที่ที่มีสิ่งรบกวนทางเสียงและสายตาน้อย มองหาบรรยากาศที่ส่งเสริมจินตนาการและไม่มีผู้คนพลุกพล่าน ถ้าพื้นที่ใช้ร่วมกันให้จองพื้นที่ก่อนแต่เนิ่น ๆ

คุณสามารถเล่น D&D ได้ทุกที่ที่คุณรวมตัวกันได้แบบออนไลน์ เช่นวีดีโอคอลไปจนถึงระบบโต๊ะเกมเสมือน (virtual tabletop) สุดล้ำ

การกำหนดเวลาเล่นเกม

บางครั้งสิ่งที่ยากที่สุดในการดำเนินเกมคือการหาเวลาที่ทุกคนพร้อมเล่นด้วนกัน บางกลุ่มเล่นกัน 2-3 ชั่วโมงทุกสัปดาห์ ขณะที่บางกลุ่มเล่นกันหนึ่งวันเต็มในหนึ่งเดือน พยายามกำหนดเวลาเล่นให้เหมาะกับกลุ่มของคุณ

สำหรับกลุ่มใหม่ การกำหนดเวลาเล่นแบบเซสชันเดียวต่อเกม (มักจะเรียกกันว่า “วัน-ช็อต (one-shot)”) มักจะเหมาะสมเพราะเป็นการให้ทุกคนได้ทดลองเล่นก่อน ถ้าทุกคนมีประสบการณ์ที่ดีจากหนึ่งเซสชัน มันก็ง่ายที่จะให้ทุกคนมาเล่นกันต่อในเกมยาวหลังจากนั้น

บางครั้งหากเวลาไม่ตรงกันมันก็เป็นสิ่งที่หลีกเลี่ยงไม่ได้ “ขนาดกลุ่มเล่นเกม (Group Size)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) มีคำแนะนำในการจัดการสถานการณ์ที่อาจมีผู้เล่นบางคนไม่ได้มาเล่นในบางเซสชัน

ลูกเต๋า (Dice)

คุณต้องมีชุดลูกเต๋าหลายเหลี่ยม: d4, d6, d8, d10, d12, และ d20 มันจะช่วยได้มากหากคุณมีอย่างน้อย 2 ลูกในแต่ละชนิด ผู้เล่นแต่ละคนก็ควรมีชุดลูกเต๋าของตัวเองด้วย

ลูกเต๋าแบบดิจิตัลก็มีให้ใช้เหมือนกัน แบบอย่างง่ายก็เป็นเว็บไซต์ที่มีในอินเตอร์เน็ต แอ็พมือถือเฉพาะสำหรับทอยลูกเต๋าก็มีในแอพสโตร์ และโปรแกรมโต๊ะเกมเสมือน (virtual tabletop) ก็มักจะมีระบบทอยลูกเต๋าอยู่ด้วย

อุปกรณ์สำหรับจดบันทึก

ทุกคนต้องมีวิธีอะไรสักอย่างที่จะจดบันทึกสิ่งต่าง ๆ ระหว่างทุกรอบในการต่อสู้ บางคนต้องการที่จะจดบันทึก ลำดับการต่อสู้ (Initiative), ฮิตพอยต์ (Hit Points), สภาวะ, และข้อมูลสำคัญอื่น ๆ ผู้เล่นมักจะจดบันทึกสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นในการผจญภัย และอย่างน้อยหนึ่งในผู้เล่นควรจะบันทึกคำใบ้และสมบัติต่าง ๆ ที่ตัวละครหามาได้

ชีตตัวละคร (คาแร็กเตอร์ชีท - Character Sheets)

ผู้เล่นต้องมีวิธีในการบันทึกข้อมูลสำคัญเกี่ยวกับตัวละครที่เล่น กระดาษธรรมดาก็ใช้งานได้ แต่ผู้เล่นจะพบว่าใช้ชีทออฟฟิเชียลหรือชีทที่แฟนเกมออกแบบมาจะทำให้จัดการข้อมูลได้มีประสิทธิภาพมากกว่า ดิจิตัลชีทก็มีหลากหลายสามารถใช้ได้หากคุณเล่นออนไลน์หรือใช้อุปกรณ์ดิจำตัลบนโต๊ะได้

บันทึกแคมเปญ

ตลอดหนังสือเล่มนี้คุณจะพบกับชีทในการบันทึกสิ่งต่าง ๆ ที่คุณสามารถใช้มาช่วยให้การเป็น DM ของคุณง่ายขึ้น มันมีตั้งแต่ชีทที่คุณใช้ในการบันทึกเหล่า NPC หรือรายละเอียดชุมชนต่าง ๆ ในเกมของคุณ ไปจนถึงบันทึกที่ให้คุณแน่ใจว่าคุณมอบไอเท็มเวทย์มนต์ให้นักผจญภัยอย่างเหมาะสม ชีทเหล่านี้สามารถใช้เป็นพื้นฐานของการบันทึกแคมเปญ และสามารถช่วยคุณในการวางแผนการผจญภัยและสร้างโลกเกมของคุณได้ คุณสามารถสแกนหรือถ่ายเอกสารชีทเหล่านี้เพื่อใช้ส่วนตัวได้ และคุณสามารถดาวน์โหลดได้จากบท ชีทบันทึก (Tracking Sheets)

สิ่งมีประโยชน์อื่น ๆ

สิ่งอื่น ๆ ที่หลากหลายสามารถเพิ่มพูนประสบการณ์การเล่นเกมของคุณให้สนุกยิ่งขึ้นได้ หลายอย่างอาจเป็นเวอร์ชันดิจิตัล ทำให้คอมพิวเตอร์, แท็บเล็ต, และสมาร์ทโฟนเป็นสิ่งจำเป็นในการเล่นบางเกมและจำเป็นสำหรับผู้เล่น

ฉากของ DM (DM Screen)

ฉาก DM นี้จะเป็นตัวบังหนังสือ, บันทึก, และการทอยลูกเต๋าของคุณจากผู้เล่น (ดูบท “ต้องแน่ใจว่าทุกคนสนุก” ในส่วนท้ายของบทนี้สำหรับข้อมูลว่าเมื่อไรและทำไมคุณถึงควรซ่อนการทอยลูกเต๋าของคุณ) ฉาก DM ส่วนใหญ่จะมีภาพสวย ๆ ในด้านนอกที่ผู้เล่นจะเห็นและมีกฏและข้อมูลย่อในอีกด้านหนึ่ง บางคนก็ทำฉากจากไม้หรือมีปฏิมากรรมประดับสวยงามเพิ่มอารมณ์ให้ผู้เล่น

คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องมีฉากนี้สำหรับซ่อนสิ่งต่าง ๆ ถ้าคุณเล่นออนไลน์ แต่มันก็จะช่วยได้มากหากคุณมีที่ที่คุณจะดูข้อมูลต่าง ๆ ได้อย่างรวดเร็ว เช่นนิยามของสภาวะ, แอ็คชันปกติ, และกฏอื่น ๆ DM บางคนก็มีฉาก DM ไว้ด้วยแม้จะเล่นผ่านคอมพิวเตอร์ โต๊ะเกมเสมือนก็มักจะมีข้อมูลเหล่านี้ไว้ให้ใช้ด้วย

หนังสือเนื้อเรื่องการผจญภัย (Adventures) และ หนังสือข้อมูลเกม (Sourcebooks)

นอกเหนือจากหนังสือกฏหลัก (core rulebooks) 3 เล่มแล้ว ยังมีเนื้อหาอีกมากมายที่ตีพิมพ์จากวิซาร์ดออฟเดอะโคสท์ (Wizards of the Coast) และสำนักพิมพ์อื่น หนังสือเนื้อเรื่องการผจญภัย (adventure) จะมีจุดดึงดูดให้ผจญภัย (hooks), พล็อตเรื่อง, แผนที่, และการเผชิญหน้าต่าง ๆ ที่คุณสามารถนำไปใช้ในเกมได้ หนังสือข้อมูลเกม (sourcebook) จะมีหลายสิ่งเช่นตัวเลือกใหม่ในการสร้างตัวละคร, มอนสเตอร์ใหม่, และแรงบันดาลใจในการสร้างเรื่องราวการผจญภัยและแคมเปญของคุณเอง คุณสามารถเล่น D&D โดยไม่มีสิ่งเหล่านี้เลยก็ได้ แต่ DM (และผู้เล่น) หลายคนพบว่ามีก็ดีนะ ทำให้เรื่องราวมีรายละเอียดและตื่นเต้นมากขึ้น

แบทเทิลกริด (Battle Grid) และโมเดลจิ๋ว (Miniatures)

DM บางคนใช้แบทเทิลกริดและโมเดลจิ๋วในการรันการต่อสู้ ซึ่งช่วยให้ผู้เล่นมองเห็นภาพเมื่อเล่นกันบนโต๊ะ แบทเทิลกริดอาจเป็นผืนพลาสติกไวนิลที่พิมพ์ลายตาราง, เป็นไวท์บอร์ดที่มีตาราง, กระดานตัดกระดาษ, กระดาษกริดขนาดใหญ่, หรือโปสเตอร์แผนที่ สิ่งเหล่านี้สามารถใช้เป็นแบทเทิลกริดได้ ช่องตารางกริดควรจะมีขนาด 1 ตารางนิ้ว

คุณยังต้องใช้โมเดลจิ๋วทำจากพลาสติกหรือโลหะเพื่อเป็นตัวแทนตัวละครและมอนสเตอร์ในเกม แต่คุณอาจจะใช้เหรียญ, ลูกเต๋า, กระดาษตัด, หรือแม้แต่เศษเทียนก็ได้ถ้าไม่มีโมเดลจิ๋ว

ซอร์ฟแวร์มากมายที่ออกแบบมาเพื่อใช้เล่น D&D แบบออนไลน์จะมีแบทเทิลกริด ถึงแม้จะไม่มีเครื่องมือเหล่านี้ การเล่น D&D แบบออนไลน์หลายเกมก็ใช้โปรแกรมแชร์หน้าจอร่วมกับโปรแกรมวาดรูป ในการแชร์ไวท์บอร์ดหรือเครื่องมืออื่นที่ใช้เป็นแบทเทิลกริดอย่างง่าย DM บางคนสะดวกจะใช้ซอร์ฟแวร์ที่ให้พวกเขาได้ควบคุมแสงและแสดงให้ผู้เล่นเห็นสิ่งที่พวกเขาสามารถเห็นได้ บางคนก็รู้สึกว่าซอร์ฟแวร์ที่ซับซ้อนนั้นขัดขวางการเล่นเกม เลือกใช้อุปกรณ์ที่เหมาะกับกลุ่มของคุณ

การ์ดเสริมต่าง ๆ

ผู้เล่นและ DM บางคนพบว่าการมีการ์ดข้อมูลนั้นช่วยในการเล่นเกมได้มาก คุณสามารถซื้อ (หรือทำ) การ์ดแต่ละคาถา, ไอเท็มเวทย์มนต์, สแต็ทบล็อกของมอนสเตอร์, รายการกฏ, และข้อมูลอื่น ๆ เพื่อให้ค้นหาได้ง่าย

การเตรียมเซสชัน

ยิ่งคุณเตรียมตัวก่อนเกมของคุณมากเท่าไร เกมก็ยิ่งจะลื่นไหลมากขึ้นเท่านั้น เพื่อเป็นการหลีกเลี่ยงการเตรียมตัวน้อยหรือมากเกินไป ให้ใช้แนวทางเตรียมตัวสำหรับหนึ่งชั่วโมงด้านล่างนี้และจัดลำดับความสำคัญของสิ่งที่คุณต้องเตรียมโดยขึ้นอยู่กับเวลาที่คุณมี

แนวทางเตรียมตัวสำหรับหนึ่งชั่วโมง (The One-Hour Guideline)

เซสชัน (คาบเวลา (Session) คล้ายกับคาบเรียน) การเล่นเกม D&D หนึ่งมักจะเริ่มด้วยการพูดคุยเรื่องนอกเกมเป็นการผ่อนคลายของทุกคนก่อนเล่น เมื่อเริ่มเซสชัน กลุ่มเล่นเกมส่วนใหญ่จะทำสำเร็จอย่างน้อยสามอย่างระหว่างการเล่นหนึ่งชั่วโมง โดย “สิ่งที่ทำสำเร็จ” นั้นอาจหมายถึงดังนี้:

- สำรวจสถานที่เช่นห้องโถงในปราสาทหรือถ้ำ

- สนทนากับสิ่งมีชีวิตทรงปัญญา

- บรรลุฉันทามติในประเด็นที่ขัดแย้งกัน

- แก้ปัญหาเชาว์หรือปริศนา

- เอาตัวรอดจากกับดักมรณะ

- ต่อสู้ในการเผชิญหน้าที่ไม่ยากนัก

การต่อสู้ที่ยากขึ้นอาจจะนับเป็นสองหรือสามสิ่ง และการเจรจาต่อรองที่ตึงเครียดอาจใช้เวลาทั้งชั่วโมงเลยก็ได้

เวลาในการเตรียมการ

แนวทางด้านล่างนี้สามารถช่วยคุณในการเตรียมเซสชันสำหรับเล่นเนื้อเรื่องการผจญภัยที่พิมพ์ขายได้

การเตรียมภายในหนึ่งชั่วโมง

ถ้าคุณใช้เวลาหนึ่งชั่วโมงต่อสัปดาห์ในการเตรียมเกมของคุณ ให้ทำตามขั้นตอนนี้:

ขั้นที่ 1 ให้เน้นที่เรื่องราวของการผจญภัย อ่านหรืออ่านทวนบทนำและข้อมูลความเป็นมาของการผจญภัย สร้างรายการหัวข้อของจุดสำคัญของโครงเรื่องเพื่อให้แน่ใจว่าเรื่องราวจะดำเนินไปอย่างสอดคล้องกัน

ขั้นที่ 2 กำหนดการเผชิญหน้า (encounter) ที่คุณต้องการให้มี และพิจารณาว่ามีความเป็นไปได้แค่ไหนที่ผู้เล่นจะเจอได้ จัดกลุ่มแต่ละเหตุการณ์เป็น “เจอแน่นอน”, “อาจจะได้เจอ”, หรือ “ไม่น่าจะได้เจอ”

ขั้นที่ 3 รวบรวมแผนที่ที่คุณต้องใช้สำหรับการเผชิญหน้าที่ต้องมีแน่ ๆ และที่เป็นไปได้ว่าจะมี ต่อมาใช้เวลาที่เหลือไปเตรียมการเผชิญหน้า ตามด้านล่างนี้

สำหรับการเผชิญหน้าแบบการต่อสู้ ให้ตรวจสอบกลยุทธ์ของมอนสเตอร์และสแต็ทบล็อกหรือรายละเอียดของมอนสเตอร์แต่ละชนิด จดกฏพิเศษที่ต้องใช้ในการต่อสู้

สำหรับการเผชิญหน้าแบบปฏิสัมพันธ์ทางสังคม ให้จดข้อมูลเกี่ยวกับตัวละครที่ไม่ใช่ผู้เล่น (nonplayer characters (NPCs)) ที่ผู้เล่นต้องเจอ ดูบุคลิกภาพ, เป้าหมาย, และกลยุทธ์ในการสื่อสารตอบสนอง

สำหรับการเผชิญหน้าแบบการออกสำรวจ บันทึกเงื่อนงำหรือข้อมูลที่ตัวละครน่าจะได้รับ และดูกฏพิเศษที่อาจต้องใช้ในการออกสำรวจ

ขั้นที่ 4 พิจารณาว่าแต่ละการเผชิญหน้าในกลุ่มที่เกิดขึ้นอย่างแน่นอนนั้นมีความเกี่ยวข้องกับแรงผลักดันของผู้เล่นอย่างไร (ดูบท “รู้จักผู้เล่นของคุณ (Know Your Players)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide)) ลองคิดถึงสิ่งที่คุณสามารถเพิ่มลงไปเพื่อให้พวกเขาสนใจได้ ตัวอย่างเช่น การต่อสู้ที่อาจจะนำไปสู่การเจรจาต่อรองที่เข้มข้นที่ออกแบบไว้สำหรับผู้เล่นที่ชอบการมีปฏิสัมพันธ์ทางสังคม

ขั้นที่ 5 ดูการเผชิญหน้าในกลุ่มอาจจะได้เจอแบบคร่าว ๆ

การเตรียมการภายในสองชั่วโมง

ใช้การเตรียมการหนึ่งชั่วโมงและเพิ่มขั้นตอนต่อไปนี้

ชั้นที่ 6 ให้ดูรายละเอียดของการเผชิญหน้าในกลุ่มอาจจะได้เจอ

ขั้นที่ 7 ให้ใช้เวลาที่เหลือในการเตรียมสิ่งช่วยเหลือในการด้นสด (ดูบท “คำตอบแบบด้นสด (Improvising Answers)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide))

การเตรียมการภายในสามชั่วโมง

ถ้าคุณมีเวลาเตรียม 3 ชั่วโมง ให้เพิ่มขั้นตอนเหล่านี้:

ขั้นที่ 8 ให้ดูการเผชิญหน้าในกลุ่มไม่น่าจะได้เจอแบบคร่าว ๆ

ขั้นที่ 9 สร้างการเผชิญหน้าใหม่ที่ออกแบบให้เจาะจงไปที่ผู้เล่นหนึ่งคน หรือปรับการเผชิญหน้าที่มีอยู่ให้มีความเกี่ยวเนื่องกับเป้าหมายหรือแรงผลักดันของตัวละคนของผู้เล่นนั้น เมื่อเล่นกันหลายเซสชันให้ทำแบบนี้สำหรับผู้เล่นทุกคน

จะรันเซสชันอย่างไร

ในส่วนนี้จะอธิบายว่าเราจะรันเซสชันอย่างไร ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) มีรายละเอียดเรื่องทำอย่างไรที่จะรวมเซสชันการเล่นไปเป็นการผจญภัย และการผจญภัยไปสู่แคมเปญ

การเล่าย้อนเรื่อง

เริ่มเซสชันการเล่นหลังจากเซสชันแรกด้วยการย้อนเล่าเรื่องจากเซสชันที่แล้วว่ามีอะไรเกิดขึ้นบ้าง การย้อนเล่าเรื่องจะช่วยให้ผู้เล่นฟื้นความจำเกี่ยวกับเรื่องราวได้ มันยังให้ข้อมูลสำคัญ ๆ แก่ผู้เล่นที่อาจจะไม่ได้เล่นเซสชันที่แล้วด้วย คุณสามารถเป็นคนเล่าเองหรือจะเชิญให้ผู้เล่นคนอื่นเป็นคนเล่าก็ได้ แต่ละแบบจะได้ผลต่างกัน:

DM เป็นคนเล่า คุณเป็นคนเล่าเองถ้าคุณมีข้อมูลเฉพาะบางอย่างที่คุณอยากเสริมหรือถ้าคุณต้องการให้ข้อมูลในส่วนที่จะมีผลกับการเล่นต่อไป

ผู้เล่นเป็นคนเล่า ให้ผู้เล่นเป็นคนเล่าย้อนถ้าคุณต้องการรู้ว่าพวกเขาคิดว่าอะไรสำคัญหรือเป็นการเรียนรู้ว่าพวกเขาได้อะไรจากเกมที่แล้วบ้าง ถ้าผู้เล่นพลาดสิ่งสำคัญไปคุณก็สามารถเสริมได้

การเผชิญหน้า (Encounters)

เซสชันการเล่น D&D โดยปกติแล้วจะเป็นการรวมกันของชุดการเผชิญหน้าต่าง ๆ เหมือนกับซีนในภาพยนต์หรือละครซีรี่ส์ ในแต่ละการเผชิญหน้านั้น มีโอกาสที่ DM จะอธิบายสิ่งมีชีวิตหรือสถานที่และเป็นโอกาสที่ผู้เล่นจะตัดสินใจเลือกสิ่งต่าง ๆ การเผชิญหน้าเกิดขึ้นได้ในการสำรวจ (exploration) (การมีปฏิสัมพันธ์กับสิ่งแวดล้อม รวมถึงปริศนาต่าง ๆ), การมีปฏิสัมพันธ์ทางสังคมกับสิ่งมีชีวิต, หรือการต่อสู้ ในส่วนต่อไปจะอธิบายรายละเอียดว่าการเผชิญหน้าจะเกิดขึ้นได้อย่างไรในสามชั้นตอน

ชั้นที่ 1: อธิบายสถานการณ์

เมื่อเป็น DM คุณจะเป็นคนตัดสินใจว่าจะบอกข้อมูลกับผู้เล่นมากน้อยแค่ไหนและเมื่อใด ข้อมูลทั้งหมดที่ผู้เล่นต้องใช้ในการตัดสินใจนั้นมาจากคุณ ภายใต้กฏของเกมและความรู้และประสาทสัมผัสที่มีจำกัดของตัวละคร ให้บอกผู้เล่นทุกอย่างที่พวกเขาควรต้องรู้

เนื้อเรื่องการผจญภัยที่พิมพ์ขายมักจะมีข้อความเหมือนในกล่องข้อความนี้ ซึ่งหมายความว่าให้คุณอ่านออกเสียงให้ผู้เล่นฟังเมื่อตัวละครของพวกเขามาถึงสถานที่นี้หรือเผชิญหน้ากับเหตุการณ์นี้เป็นครั้งแรกดังที่อธิบายในข้อความ มันมักจะอธิบายรายละเอียดสถานที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นรู้ว่าอะไรเกิดขึ้นและพอจะเข้าใจตัวเลือกที่ตัวละครของพวกเขาจะมีได้

ไม่ว่าคุณจะรันการผจญภัยที่พิมพ์ขายหรือเป็นการผจญภัยที่คุณสร้างขึ้นเอง คำอธิบายเริ่มแรกของห้องหรือสถานการณ์นั้นควรจะเน้นไปที่สิ่งที่ตัวละครสามารถรับรู้ได้ คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องอธิบายทุกอย่างในคราวเดียว ผู้เล่นส่วนใหญ่เริ่มจะเสียสมาธิหลังจากอธิบายไปเพียงสามประโยค เมื่อตัวละครสำรวจห้อง, เปิดลิ้นชักและหีบ, และตรวจสอบสิ่งต่าง ๆ อย่างใกล้ชิด, จึงค่อยเพิ่มรายละเอียดว่าตัวละครพบกับอะไรบ้าง

บท “การบรรยายเรื่อง (Narration)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) มีรายละเอียด คำแนะนำและตัวอย่างของการบรรยายเรื่อง

ขั้นที่ 2: ให้ผู้เล่นได้พูด

เมื่อคุณบรรยายสถานการณ์จบแล้ว ถามผู้เล่นว่าตัวละครของพวกเขาต้องการทำอะไร จดสิ่งที่ผู้เล่นพูดและตัดสินใจว่าจะตอบสนองต่อการกระทำของพวกเขาอย่างไร ถามคำถามได้หากต้องการข้อมูลเพิ่ม

บางครั้งผู้เล่นอาจจะให้คำตอบเป็นกลุ่ม: “พวกเราจะผ่านเข้าประตูไป” หรือบางทีผู้เล่นคนหนึ่งอาจจะต้องการทำบางอย่าง คนหนึ่งอยากลองหาหีบสมบัติขณะที่คนอื่นไปสำรวจตู้หนังสือ นอกการต่อสู้ ตัวละครไม่ต้องทำกิจกรรมผ่านเทิร์น แต่คุณก็อาจจะให้โอกาสผู้เล่นแต่ละคนในการบอกว่าตัวละครของตนทำอะไร และคุณสามารถตัดสินใจตอบสนองต่อแอ็คชันของทุกคนได้ ในการต่อสู้ ทุกคนต้องใช้เทิร์นตามลำดับการต่อสู้

ขั้นที่ 3: บรรยายว่าอะไรเกิดขึ้น

หลังผู้เล่นบรรยายแอ็คชันของพวกเขาแล้ว มันเป็นงานของ DM ที่จะตอบสนองต่อแอ็คชันเหล่านั้น โดยใช้แนวทางจากกฏและการผจญภัยที่คุณเตรียมมา ดังนั้นคุณจะตัดสินใจยังไงล่ะ? ลองคิดถึงความเป็นไปได้เหล่านี้:

ไม่ต้องใช้กฏก็ได้ บางครั้ง การตอบสนองต่อสถานการณ์นั้นง่ายมาก ถ้านักผจญภัยต้องการข้ามห้องว่างและประตูเปิดอยู่ คุณสามารถบอกไปได้เลยว่าประตูเปิดอยู่และบรรยายว่ามีอะไรอยู่ถัดไป (อาจจะเทียบกับแผนที่หรือโน๊ตของคุณ)

ฝ่าอุปสรรคสู่ความสำเร็จ แม่กุญแจ, ทหารยาม, หรืออุปสรรคอื่นอาจจะคอยขัดขวางนักผจญภัยในการทำภาระกิจ ในกรณีนั้นโดยปกติคุณจะใช้การ ทอยทดสอบ D20 (D20 Test) มักจะเป็นการทดสอบความสามารถ ตัวอย่างเช่น นักผจญภัยต้องทอยทดสอบความคล่องแคล่ว (Dexterity) ทักษะ มือไว (Sleight of Hand) เพื่อตัดสินว่าสะเดาะกุญแจได้หรือไม่ ขณะที่การทอยทดสอบเสน่ห์ (Charisma) ทักษะ การโน้มน้าว (Persuasion) และเงินเหรียญจำนวนหนึ่งอาจจะต้องใช้ในการติดสินบนทหารยาม บท “การติดสินหาผลลัพท์ (Resolving Outcomes)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) ให้แนวทางในการใช้การทอยทดสอบ D20 และเครื่องมืออื่นในการหาผลลัพท์ของแอ็คชันของตัวละคร

การสวมบทบาท เมื่อผู้เล่นมีปฏิสัมพันธ์กับสิ่งมีชีวิตอื่น, ให้สวมบทบาทสิ่งมีชีวิตนั้นโดยอิงกับทัศนคติ เป็นมิตร (Friendly), ไม่แตกต่าง (Indifferent), or เป็นศัตรู (Hostile) ลองด้นสดโดยอิงกับข้อมูลที่คุณรู้เกี่ยวกับสิ่งมีชีวิตนั้น, สิ่งที่มันรู้, และแรงผลักดันของมัน และแสดงเป็นสิ่งมีชีวิตนั้นโดยบรรยายไปด้วยว่าเกิดอะไรขึ้น (ดูบท “การรันการปฏิสัมพันธ์ทางสังคม (Running Social Interaction)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) สำหรับคำแนะนำที่น่าสนใจ)

ครั้งละหนึ่งแอ็คชัน กฏเกี่ยวกับแอ็คชัน จำกัดจำนวนสิ่งที่ตัวละครสามารถทำได้ในช่วงเวลาหนึ่ง การจำกฏเหล่านั้นไว้จะช่วยในการติดสินใจในสถานะการได้มาก

การต่อสู้ ในการต่อสู้ หลายสถานการณ์เกี่ยวข้องกับการทอยโจมตีหรือการทอยป้องกัน กฏในการต่อสู้สามารถช่วยคุณในการตัดสินใจเกี่ยวกับประสิทธิภาพของแอ็คชันของตัวละคร บท “การรันการต่อสู้ (Running Combat)” มีคำแนะนำเกี่ยวกับการจัดการการต่อสู้

การใช้คาถา ถ้าตัวละครร่ายคาถา คุณสามารถให้ผู้เล่นเป็นคนบอกคุณว่าคาถาทำอะไรและจะตัดสินผลลัพท์อย่างไร ถ้ามีคำถามเกิดขึ้น ให้คุณอ่านข้อความรายละเอียดของคาถาด้วยตัวคุณเอง สิ่งที่คาถาทำได้นั้นมักจะเขียนไว้อย่างชัดเจน กฏการใช้คาถา แบบทั่วไปก็มีระบุถึงการตัดสินผลของคาถา

กฏที่ระบุเฉพาะจะอยู่เหนือกว่ากฏทั่วไป กฏทั่วไปจะใช้เป็นปกติในทุกส่วนของเกม แต่เกมก็ยังมีคุณสมบัติคลาส, คาถา, ไอเท็มเวทย์มนต์, ความสามารถของมอนสเตอร์, และสิ่งอื่นที่สามารถขัดแย้งกับกฏทั่วได้ เมื่อกฏเฉพาะและกฏทั่วไปขัดแย้งกัน ให้กฏเฉพาะเป็นฝ่ายชนะ ตัวอย่างเช่น กฏทั่วไประบุว่าการโจมตีด้วยอาวุธระยะประชิดนั้นจะใช้ค่าโมดิไฟเออร์ความแข็งแกร่ง (Strength) ของตัวละคร แต่ถ้ามีคุณสมบัติหนึ่งบอกว่า ตัวละครนั้นสามารถโจมตีด้วยอาวุธระยะประชิดได้โดยการใช้ค่าความสามารถเสน่ห์ (Charisma) กฏเฉพาะนี้จะถูกนำไปใช้แทนที่กฏทั่วไป

ในการบรรยายผลลัพท์ พยายามให้คำอธิบายที่ออกรสออกชาติขณะที่สื่อสารอย่างชัดเจนว่ามีอะไรเกิดขึ้นในภาษาของเกม ดูบท “การบรรยายในการต่อสู้ (Narration in Combat)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) สำหรับคำแนะนำและตัวอย่าง

การบรรยายผลลัพท์มักจะทำให้เกิดจุดตัดสินใจใหม่ให้ผู้เล่นอื่น ซึ่งจะทำให้การไหลของเกมกลับมาที่ขั้นตอนที่ 1

เวลาที่ผ่านไป

เกมนั้นมีจังหวะและการไหลที่มีช่วงเวลาของแอ็คชันและความตื่นเต้นกระจายคละกันไปกับช่วงเวลาที่สงบราบเรียบ เหมือนภาพยนต์ที่มีช่วงที่เวลาผ่านไประหว่างซีน เมื่อการเผชิญหน้าจบลง คุณสามารถขยับไปสู่ช่วงถัดไป คุณสามารถรวบการเดินทางหลายชั่วโมงด้วยการบรรยายสรุปอย่างรวดเร็ว (ดูบท “การเดินทาง (Travel)” สำหรับคำแนะนำเพิ่มเติม) เหมือนกันกับถ้าช่วงการพักผ่อนไม่มีเหตุการณ์อะไร คุณบอกผู้เล่นได้เลยว่าพักเสร็จแล้วและไปต่อ อย่างปล่อยให้ผู้เล่นเสียเวลาไปกับการปรึกษากันว่าใครจะทำอาหารเย็นเว้นแต่ว่าพวกเขาอยากลองทำดู คุณสามารถผ่านรายละเอียดที่ไม่สำคัญและกลับไปสู่ฉากแอ็คชันได้ทันที

คอยดูว่าผู้เล่นต้องการปรึกษากันเกี่ยวกับเหตุการณ์ในเกม, ใช้เวลาวางแผน, และมีบทสนทนาระหว่างตัวละคร คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องมีส่วนร่วมในทุกการสนทนาเว้นแต่ว่าพวกเขาต้องการถามคำถาม เรียนรู้ที่จะมองเห็นเวลาที่คุณสามารถพักได้แม้เป็น DM และกลับมาทำหน้าที่ได้ทันทีเมื่อทุกคนพร้อมไปต่อ

หาเวลาพัก

เมื่อคุณจบการต่อสู้ที่ยาวนานหรือซีนที่เข้มข้นตึงเครียด หรือถ้าคุณต้องการเวลาในการขบคิด, ให้หยุดพักก่อน ให้สมองของคุณได้ปรับโฟกัสใหม่, ผ่อนคลาย, หรือเตรียมการเผชิญหน้าชุดถัดไป มันไม่เป็นไรเลยที่จะปล่อยให้ผู้เล่นค้างเติ่งอยู่แบบนั้นขณะที่คุณพักไปคิดถึงสิ่งที่จะเกิดขึ้นจากแอ็คชันของพวกเขา

การจบเซสชัน

พยายามอย่าจบเซสชันระหว่างการเผชิญหน้า มันยากที่จะบันทึกข้อมูลต่าง ๆ เช่น ลำดับการต่อสู้ (Initiative) และรายละเอียดอื่นที่เกิดขึ้นระหว่างรอบการต่อสู้ ข้อยกเว้นสำหรับคำแนะนำนี้คือเมื่อคุณจงใจจะจบเซสชันแบบอยากให้ติดตามตอนต่อไป เป็นเวลาที่เรื่องราวหยุดไว้ตอนที่มีเหตุการสำคัญเกิดขึ้นหรือมีเรื่องประหลาดใจที่จะทำให้เรื่องราวกลับตาลปัติ สิ่งเหล่านี้ทำให้ผู้เล่นประหลาดใจและตื่นเต้นที่จะเล่นในเซสชันถัดไป

ถ้าผู้เล่นคนหนึ่งไม่ได้มาเล่นและคุณให้ตัวละครนั้นออกจากกลุ่มผจญภัยไประยะหนึ่ง ให้คิดถึงวิธีที่จะนำตัวละครกลับมาเมื่อผู้เล่นกลับมาเล่นด้วย บางครั้งการค้างเรื่องก็มีประโยชน์ ตัวละครที่พุ่งเข้ามาช่วยนักผจญภัยในยามคับขันก็คือเพื่อนนักผจญภัยที่หายไปของพวกเขานี่เอง

ให้เวลาสักระยะหนึ่งในช่วงตอนจบเซสชันให้ทุกคนได้พูดคุยกันเกี่ยวกับเหตุการณ์ในเกม ถามผู้เล่นของคุณว่าพวกเขาชอบตรงไหนและอะไรที่อยากให้มีอีก บันทึกสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นและสถานการในช่วงจบเซสชัน จะได้เอาไว้เป็นข้อมูลในการเตรียมเซสชันต่อไป

DM ทุกคนมีเอกลักษณ์

ไม่มี DM คนไหนที่รันเกมเหมือนกันเป๊ะ และนั่นเป็นสิ่งที่ควรจะเป็น! คุณจะเป็น DM ที่ประสบความสำเร็จมากที่สุดถ้าคุณเลือกสไตล์การเล่นที่เหมาะสมกับคุณและผู้เล่นของคุณ

กฏแห่งความสนุก

D&D เป็นเกมที่ทุกคนควรจะสนุกในการเล่น ทุกคนจะแบ่งปันความรับผิดชอบร่วมกันในการผลักดันให้เกมดำเนินไป และทุกคนผู้ร่วมสร้างความสนุกเมื่อพวกเขาปฏิบัติต่อผู้อื่นอย่างให้เกียรติและระมัดระวัง: ให้พูดคุยถึงสิ่งที่ผู้เล่นขัดแย้งกันและจำไว้ว่าการทะเลาะทุ่มเถียงจะทำให้หมดสนุกได้

ผู้คนมักจะมีไอเดียที่แตกต่างกันมากกมายเกี่ยวกับว่าอะไรที่ทำให้เกม D&D สนุก “ทางที่ถูก” ในการเล่น D&D นั้นคือวิธีที่คุณและผู้เล่นเห็นพ้องกันและสนุกด้วยกัน ถ้าทุกคนมาที่โต๊ะและเตรียมตัวมามีส่วนร่วมกับเกม ก็เป็นไปได้ว่าทั้งโต๊ะนั้นจะมีช่วงเวลาและความทรงจำที่ดี

สไตล์การเล่น

นี่เป็นคำถามบางส่วนที่สามารถช่วยให้คุณค้นหาสไตล์ที่เป็นเอกลักษณ์ในการเป็น DM ของคุณและลักษณะของเกมที่คุณต้องการรัน:

เน้นการต่อสู้หรือเน้นการสวมบทบาท? เกมของคุณเน้นการต่อสู้หรือมีเรื่องราวที่ลุ่มลึกด้วยรายละเอียดและมี NPC ที่มีบทบาทมากมาย?

เหมาะกับทุกวัยหรือเฉพาะผู้ใหญ่? เกมเหมาะกับทุกช่วงอายุหรือเน้นเฉพาะผู้ใหญ่?

สมจริงหรือแบบภาพยนต์? คุณชอบความสมจริงแบบเข้มข้นหรือคุณเน้นให้เกมมีความรู้สึกแบบภาพยนตร์และซูเปอร์ฮีโร่มากกว่า?

จริงจังหรือสนุกสนาน? คุณอยากให้เป็นเกมแบบจริงจังหรือตลกเฮฮา?

เตรียมเกมไว้ก่อนหรือเน้นด้นสด? คุณชอบวางแผนครบถ้วนตลอดเรื่อง หรือชอบแบบด้นสด?

เรื่องราวทั่วไปหรือมีรูปแบบ? เป็นเกมที่ผสมกันของธีมและแนวเรื่องหลายแบบ หรือมันเน้นไปที่ธีมหรือแนวเรื่องแบบเดียวเช่นสยองขวัญ?

คลุมเครือทางศีลธรรมหรือฮีโร่ผู้กล้าหาญ? คุณรับได้กับความคลุมเครือทางศีลธรรมหรือไม่ เช่นอนุญาตให้ตัวละครสำรวจว่าผลลัพท์นั้นเหมาะสมกับวิธีการหรือไม่ หรือคุณจะรู้สึกดีกว่าถ้าตรงไปที่หลักการแบบฮีโร่ เช่นความยุติธรรม, การเสียสละ, และการช่วยเหลือผู้อ่อนแอ?

กฏเฉพาะโต๊ะ (House Rules)

กฏเฉพาะโต๊ะเป็นกฏที่กำหนดขึ้นใหม่หรือเป็นการแก้ไขกฏปกติที่นำมาใช้เฉพาะในเกมของคุณเองเพื่อเพิ่มรูปแบบการเล่นให้ตรงกับที่คุณออกแบบไว้ ก่อนที่คุณจะตั้งกฏเฉพาะโต๊ะ ให้ถามตัวเองสองคำถามนี้ก่อน:

- กฏหรือการเปลี่ยนแปลงนี้จะทำให้เกมดีขึ้นใช่มั๊ย?

- ผู้เล่นจะชอบมั๊ย?

ถ้าคุณมั่นใจว่าคำตอบของทั้งสองคำถามนี้คือ ใช่ ก็ลองใช้กฏนั้นได้เลย ให้ทดลองใช้ก่อนในขั้นแรกและถามความรู้สึกของผู้เล่น ถ้าคุณลองใช้กฏเฉพาะโต๊ะแล้วทำให้เกมไม่สนกก็เอามันออกไปปรับใหม่ก่อน

บันทึกการตีความกฏ

ถ้าเกิดคำถามเกี่ยวกับการตีความกฏเกิดขึ้นในเกมของคุณ ให้บันทึกว่าคุณตัดสินใจตีความมันอย่างไร เพิ่มสิ่งนั้นเข้าไปในรายการกฏเฉพาะโต๊ะเพื่อที่คุณและผู้เล่นสามารถใช้อ้างอิงเมื่อกฏถูกนำมาใช้อีกครั้ง

บรรยากาศ

DM บางคนใช้ดนตรีที่เหมาะสมในการสร้างบรรยากาศสำหรับเซสชันเกมของพวกเขา อาจใช้ซาวด์แทร็กจากภาพยนต์ผจญภัยหรือวีดีโอเกม, แม้กระทั้งเพลงคลาสสิก, ดนตรีบรรยากาศ (ambient), หรือดนตรีสไตล์อื่นก็สามาถใช้ได้

DM บางคนปรับแสดงสว่างหรือใช้เสียงเอฟเฟค โมเดลจิ๋วและฉากไดโอรามาสามารถช่วยสร้างบรรยากาศของเกมให้ผู้เล่นได้มองเห็นเหตุการณ์ได้ ให้พูดคุยกับผู้เล่นของคุณก่อนเพราะบางคนจะรู้สึกว่าเสียงดนตรี, แสง, หรือเสียงเอฟเฟคนั้นทำให้เสียสมาธิ อาจจะไม่ชอบถูกทำให้ตกใจจากเสียงดัง หรืออาจจะต้องหลีกเลี่ยงเอฟเฟคแสงบางอย่าง

ให้คนอื่นช่วย

ถ้ามีส่วนไหนของเกมที่คุณไม่อยากรันด้วยตัวเอง ลองให้ผู้เล่นคนอื่นที่ชอบรันให้ ถ้าคุณไม่อยากทำให้การบรรยายติดขัดจากการต้องค้นหากฏที่เกี่ยวข้อง ให้ผู้เล่นคนหนึ่งรับหน้าที่เป็นผู้เชี่ยวชาญด้านกฏและมีหนังสือกฏไว้ประจำตัว ถ้าคุณไม่อยากเป็นคนจัดการลำดับการต่อสู้ ลองให้ใครสักคนทำแทนได้

เรียนรู้จากการสังเกต

หนึ่งในวิธีที่จะเรียนรู้การรันเกม D&D คือการเฝ้าสังเกต DM คนอื่นเวลาเขารันเกม DM คนอื่นสามารถแสดงให้คุณเห็นถึงบทบาทพื้นฐานของการเป็น DM ได้อย่างดี และยังเป็นแรงบันดาลใจให้คุณได้ด้วยหากมีสิ่งเจ๋ง ๆ ที่คุณนำไปใช้ในเกมของคุณเองได้

คุณสามารถใช้แนวทางด้านล่างนี้นี้ช่วยในการสังเกตเกมที่คุณกำลังดูอยู่:

การเริ่มต้นเซสชัน สังเกตว่า DM เริ่มเซสชันอย่างไร มีการเล่าทวนเรื่องราวหรือไม่?

ภาษากาย DM มีท่าทางประกอบอย่างไรบ้างเมื่อบรรยายฉากต่าง ๆ ภาษากายเขาเปลี่ยนแปลงไปอย่างไรเมื่อต้องเล่นเป็น NPC ที่แตกต่างกัน?

เสียงของ DM DM ใช้เสียงที่แตกต่างกันหรือมีกริยาท่าทางที่เปลี่ยนไปอย่างไรเมื่อเล่นเป็น NPC แต่ละตัว? DM เปลี่ยนความทุ้มแหลมของน้ำเสียงหรือจังหวะการพูดบรรยายในสถานการณ์ที่แตกต่างกันหรือไม่?

การมีส่วนร่วมของผู้เล่น ผู้เล่นมีส่วนร่วมในการสร้างโลกในเกมหรือการตัดสินใจที่จะทำให้การผจญภัยฉีกออกไปในทิศทางที่ไม่คาดหมายหรือไม่? และ DM จัดการอย่างไร?

การตีความกฏ DM อิงกับกฏมากแค่ไหนในการใช้กฏเพื่อให้ได้ผลลัพท์ DM ใช้กฏอย่างเหมาะสมกับเหตุการณ์หรือใช้ไปในทางเน้นให้เกมสนุกขึ้น

เสาหลักทั้งสาม ในเซสชันนั้นมีสัดส่วนของการต่อสู้, การออกสำรวจ, หรือการมีปฏิสัมพันธ์ทางสังคมมากน้อยแค่ไหน?

ระดับของเกมและอารมณ์ คุณจะอธิบายระดับความจริงจังและอารมณ์ของเกมอย่างไร? มันเปลี่ยนไปตลอดการเล่นหรือไม่?

วลีสุดเจ๋ง มีคำหรือประโยคอะไรในการบรรยายที่คุณชอบมากหรือไม่ (ถ้ามีให้จดลงไป)

การสร้างโลกในเกม ส่วนใดของโลกที่ DM บรรยายหรือการผจญภัยที่กระตุ้นความสนใจของคุณ

ให้แน่ใจว่าทุกคนมีความสุข

ก่อนจะเล่นเกม ถ้าคุณยังไม่ได้ทำ ให้คุณปรึกษากันกับผู้เล่นถึงประสบการณ์ที่คุณทั้งหมดคาดหวัง รวมถึงหัวข้อ, ชนิดของเนื้อเรื่อง, และพฤติกรรมที่อาจจะทำให้บางคนหมดสนุกในเกมของคุณ

ให้เกียรติซึ่งกันและกัน

ไม่ว่าคุณจะเล่นกับเพื่อนสนิทหรือกับคนแปลกหน้า มันสำคัญที่จะสร้างรากฐานความเชื่อใจและให้เกียรติ เกมที่ดีที่สุดจะเกิดขึ้นเมื่อทุกคนบนโต๊ะรู้สึกปลอดภัยที่จะพูดและได้สวมบทบาทอย่างสบายใจ

ทุกคนต้องยึดมั่นในหลักการแห่งความเคารพ การสนทนาที่ยากลำบากมักตกอยู่ที่ DM ที่จะเป็นผู้นำ แต่ก็ไม่จำเป็นต้องเป็นเช่นนั้น หากพฤติกรรมของผู้เล่นคนใดคนหนึ่งรบกวนความสนุกของคนอื่น ๆ ทุกคนก็มีส่วนได้ส่วนเสียในการช่วยแก้ไขปัญหา

การกำหนดความคาดหวัง

ก่อนที่คุณจะรวบรวมทุกคนมานั่งรอบโต๊ะ ให้ลองนำเสนอการผจญภัยที่คุณคิดว่าจะรันให้ผู้เล่นทุกคนฟังก่อน จดบันทึกความขัดแย้งที่อาจจะเกิดขึ้น ระดับเนื้อเรื่องโดยรวม และรูปแบบเนื้อเรื่องที่คุณอยากจะสำรวจ (“DM ทุกคนมีเอกลักษณ์” สามารถช่วยคุณได้ในการอธิบายเกมให้คนอื่นเข้าใจ)

การบอกผู้เล่นว่าคาดหวังอะไรได้จะเป็นการเตรียมพร้อมพวกเขาให้ได้จินตนาการถึงตัวละครแบบใดที่พวกเขาสามารถสร้างได้ และทำให้เกิดการพูดคุยเกี่ยวกับเนื้อหาที่ควรนำมาเล่นและที่ควรจะหลีกเลี่ยง คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องเปิดเผยพล็อตหลักหรือจุดหักมุมของเรื่อง แต่ให้แบ่งปันเรื่องแนวเรื่องที่คุณสนใจจะสำรวจ เรื่องราวที่เป็นแรงบันดาลใจให้คุณ และ แนวเรื่องแฟนตาซี (มีโครงร่างใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide)) ที่คุณสนใจ การเปิดเผยต่อผู้เล่นจะเป็นการอนุญาตให้พวกเขาได้ตัดสินใจ ถ้าเกมแบบนี้เป็นสิ่งที่พวกเขาอยากเล่น ซึ่งก็จะดีกว่าถ้าคุณได้รู้ก่อน

คุณต้องชัดเจนในสิ่งที่คาดหวังและต้องแน่ใจว่าคุณเข้าใจความคาดหวังของผู้เล่นด้วยเช่นกันจะทำให้การเล่นเกมลื่นไหล คุณต้องจริงจังกับความคิดเห็นและความต้องการของผู้เล่น และต้องแน่ใจว่าพวกเขาก็ทำเช่นกัน ในกรณีที่ดีที่สุด คุณจะพบกับสไตล์การเล่นที่เหมาะกับทุกคน

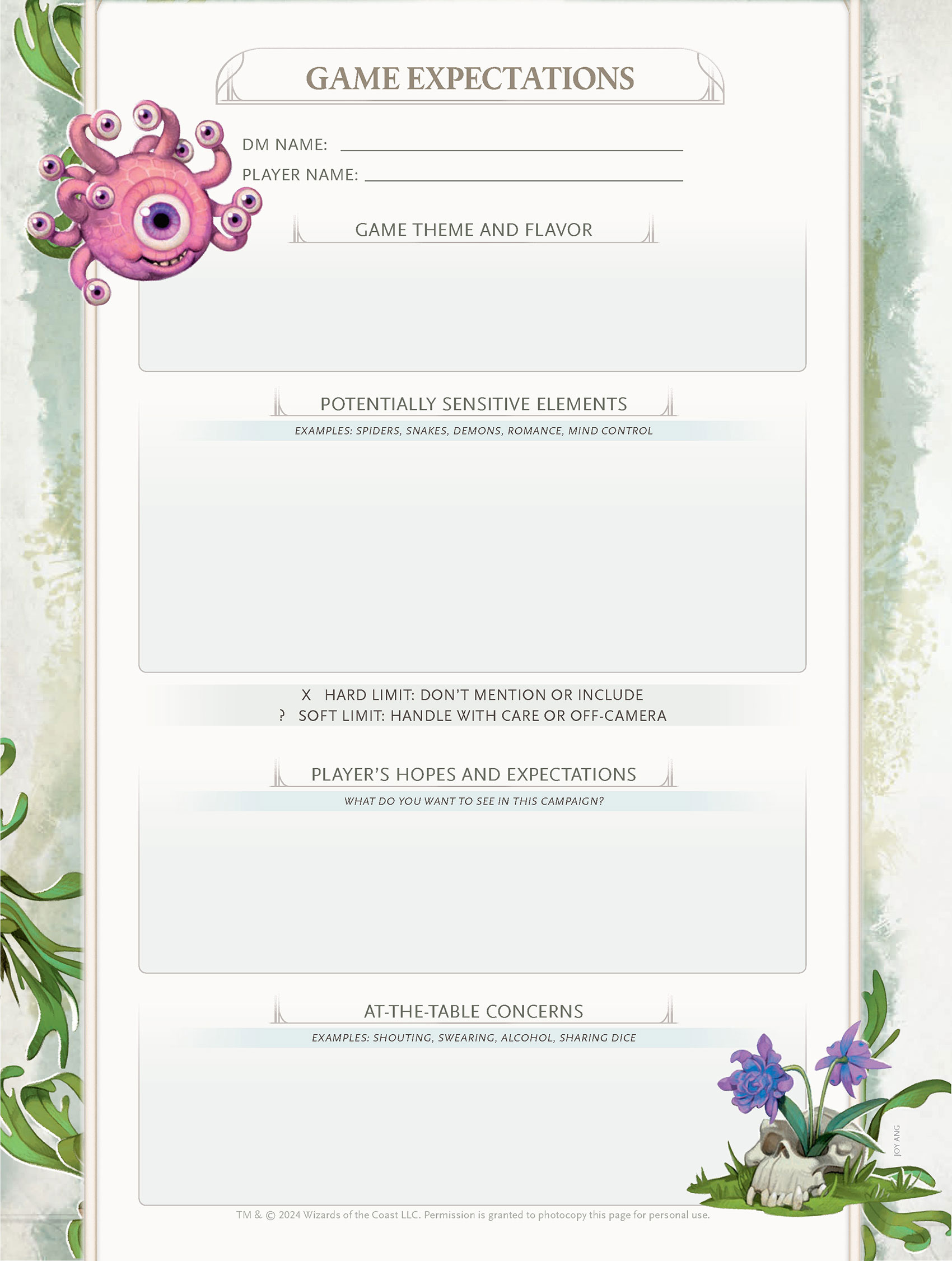

ชีทบันทึกความคาดหวังจากเกม

การใช้ชีทบันทึกความคาดหวังจากเกม

ชีทบันทึกความคาดหวังจากเกมเป็นเครื่องมือที่คุณสามารถนำมาใช้ในการตั้งความคาดหวังในช่วงก่อนเริ่มเกมเพื่อให้แน่ใจว่าเกมจะสนุกสำหรับทุกคน

ก่อนที่จะแจกชีทให้ผู้เล่น ให้คุณกรอกสองกล่องด้านบนก่อน:

ช่องรูปแบบเนื้อเรื่อง (Theme) และช่องความจริงจังของเกม ในกล่องข้อความนี้ ให้อธิบายถึงทิศทางของเกมคร่าว ๆ ที่คุณคิดเอาไว้ ดู “การกำหนดความคาดหวัง” สำหรับคำแนะนำว่าจะใส่อะไรเข้าไป

สิ่งที่เป็นเรื่องอ่อนไหว ถ้าคุณรู้ว่ามีบางอย่างในเกมที่อาจจะทำให้ผู้เล่นบางคนไม่สบายใจเกินไป ให้จดรายการเหล่านั้นลงในกล่องข้อความนี้ ดู “ขอบเขตของสิ่งที่มีได้บ้างและไม่ควรมีเลย (Hard and Soft limit)” เป็นตัวอย่าง

เมื่อใส่ข้อมูลด้านบนเรียบร้อย ถ่ายเอกสารและแจกให้ผู้เล่นทุกคน ผู้เล่นสามารถกรอกข้อมูลแบบไม่ระบุตัวตนได้ แต่ให้ของให้แต่ละคนกรอกข้อมูลสำคัญดังนี้:

ขอบเขต (Limit) ให้เขียน X สำหรับสิ่งที่ไม่อยากให้มีเลย หรือใส่เครื่องหมายคำถามสำหรับสิ่งที่พอจะมีได้ ใส่รายละเอียดถึงสิ่งที่อ่อนไหวที่อาจจะก่อปัญหา และเพิ่มสิ่งที่ควรจะต้องหลีกเลี่ยง

ความหวัง, ความคาดหวัง, และสิ่งที่เป็นห่วง ในสองกล่องสุดท้าย ให้แบ่งปันความหวังและความคาดหวังจากเกม และให้เขียนรายการสิ่งที่กังวลเกี่ยวกับพฤติกรรมขณะเล่นเกม

เก็บชีทกลับมาและรวบรวมขอบเขตแยกออกไปอีกแผ่น และให้ทุกคนในกลุ่มอ่านด้วยกัน

ขอบเขตของสิ่งที่ไม่ควรมีและสิ่งที่อาจมีก็ได้ (Hard and Soft Limits)

นอกเหนือจากแนวเรื่องและความจริงจังของความแฟนตาซีที่คุณต้องการจะสำรวจทดลองในแคมเปญของคุณแล้ว มันยังมีเรื่องสำคัญที่ต้องพูดคุยกับผู้เล่นของคุณ เกี่ยวกับหัวข้อประเด็นอ่อนไหวหรือสิ่งที่ทำให้ไม่สบายใจ มันจะช่วยได้มากหากมีการปรึกษากันในเรื่องนี้ในด้านของขอบเขตของสิ่งที่ไม่ควรมีและอาจมีได้บ้าง:

- ขอบเขตของสิ่งที่อาจมีได้บ้าง (soft limit) ใช้กับหัวข้อที่ต้องใช้อย่างระมัดระวัง เพราะอาจทำให้เกิดความวิตกกังวล, หวาดกลัว, หรือรู้สึกไม่สบายใจ

- ขอบเขตของสิ่งที่ไม่ควรมี (hard limit) เป็นสิ่งที่ไม่ควรพูดถึงหรือบรรยายในเกมเลย

DM และผู้เล่นอาจจะมีภาวะหวาดกลัว (phobias) หรือเกิดความผิดปกติเมื่อพบกับสิ่งกระตุ้น (triggers) ที่คนอื่นอาจจะไม่รู้มาก่อน สิ่งใด ๆ ในเกมหรือแนวเรื่องที่ทำให้สมาชิกในเกมรู้สึกไม่ปลอดภัย (สิ่งที่ไม่ควรมี) ต้องหลีกเลี่ยงทั้งหมด ถ้าแนวเรื่องหรือหัวข้อใดที่ทำให้ผู้เล่นกังวลแต่พวกเขาระบุว่าสามารถมีในเกมได้ (สิ่งที่อาจมีได้) ให้นำมาใช้ด้วยความระมัดระวัง แต่ถ้าเกิดเหตุการณ์ไม่พึงประสงค์ก็ต้องเตรียมพร้อมที่จะหยุดและเปลี่ยนไปเป็นอย่างอื่นทันที

ขอบเขตโดยทั่วไปในเกมจะเกี่ยวกับหัวข้อเช่น เรื่องรักใคร่ในปาร์ตี้, เพศสัมพันธ์, การเอารัดเอาเปรียบ, เหยียดเชื้อชาติ, การตกเป็นทาส, และความรุนแรงต่อเด็กและสัตว์ ขอบเขสามารถใช้กับสิ่งมีชีวิตเฉพาะอย่างได้ เช่น แมงมุม, งู, หนู, และปีศาจ ยังมีเรื่องสำคัญที่ต้องคุยกันในขอบเขตของสิ่งที่จะทำร้ายตัวละครด้วย เช่นการควบคุมจิตใจ, เวทย์มนต์, ความรู้สึกหมดทางช่วยเหลือ, และการเสียชีวิต

ซึ่งพูดได้ว่า D&D นั้นเป็นเกมที่มีความขัดแย้งและการฆ่าฟันกัน แกนหลักของเกมนั้นยากที่จะหลีกเลี่ยงได้ การได้รับความเสียหายนั้นไม่ได้จำกัดให้คุณได้หลีกเลี่ยงได้ง่ายนัก เช่นเดียวกันกับความตายของตัวละครนั้นเป็นสิ่งที่เกิดขึ้นได้ทุกเมื่อ แต่เกมก็มีทางที่จะพอหลีกเลี่ยงได้ (ดู “การตาย (Death)” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) สำหรับคำแนะนำ)

การสื่อสารในเรื่องขอบเขต ให้แน่ใจว่าทุกคนสบายใจที่จะปรึกษากันเกี่ยวกับเรื่องขอบเขตเหล่านี้ ผู้เล่นอาจจะไม่อยากพูดคุยอย่างเปิดเผย โดยเฉพาะคนที่ยังใหม่ต่อการเล่นเกมสวมบทบาท หรือยังไม่คุ้นเคยกับคนอื่น ๆ ในกลุ่มเล่นเกม วิธีหนึ่งที่จะแก้ปัญหานี้คือให้ผู้เล่นได้แบ่งปันขอบเขตนี้อย่างไม่เปิดเผยตัวตน ให้ทุกคนเขียนขอบเขตลงในแบบสอบถามแบบไม่ระบุชื่อ เช่น แบบฟอร์มความคาดหวังจากเกม ในบทนี้

รวบรวมขอบเขตให้เป็นรายการที่สามารถแบ่งปันให้ทั้งกลุ่มได้ ขอบเขตนี้ต่อรองไม่ได้และทุกคนในกลุ่มต้องเคารพเรื่องนี้ทุกคนด้วย

ในช่วงเริ่มแคมเปญเป็นเวลาที่เหมาะที่สุดที่จะมีการพูดคุยในเรื่องนี้ แต่ก็ควรมีการพูดคุยในแต่ละครั้งที่มีผู้เล่นใหม่มาร่วมเกมด้วยหรือเมื่อเนื้อเรื่องของแคมเปญเริ่มจะปรับแนวไปในทางใหม่ บางคนอาจจะข้ามเส้นและต้องให้คอยเตือนถึงขอบเขต หรือบางคนอาจจะไม่ได้บอกครบถ้วนแต่มาพบในช่วงหลังเล่นไปแล้ว ผู้เล่นสามารถเจอกับขอบเขตใหม่ได้เมื่อเนื้อเรื่องดำเนินไป ให้พูดคุยกันเมื่อเล่นไปสองสามเซสชันเพื่อให้แน่ใจว่าทุกคนสบายใจกับเรื่องราวที่พัฒนาไป อัพเดทขอบเขตของกลุ่มถ้ามีการปรับเปลี่ยน

เพิ่มรายการขอบเขต สนับสนุนให้ผู้เล่นเพิ่มรายการขอบเขตให้กับคุณ โดยส่วนตัวหรือขณะที่เล่น เพื่อที่คุณจะเพิ่มเข้าไปในรายการ ให้เชื่อใจว่าผู้เล่นรู้ดีว่าพวกเขาต้องการอะไรและอัพเดทเกมให้สอดคล้องกับสิ่งนั้น

ขอบเขตในขณะเล่น เพราะ D&D เป็นเกมที่เน้นการด้นสด เกมสามารถไปในทิศทางที่ไม่คาดคิด มันจะดีมากถ้าพวกคุณกำหนดสัญญาณที่จะสื่อสารว่าขอบเขตกำลังถูกละเมิด ทำให้คุณสามารถปรับเปลี่ยนได้อย่างทันท่วงที สัญญาณอาจจะเป็นท่าทาง (เช่นทำแขนไขว้กันเป็นรูปตัว X หรือยกมือเป็นสัญญาณ “หยุด” ก็ได้), เป็นคีย์เวิร์ดหรือวลี, แตะหรือยกวัตถุที่กำหนด, หรืออะไรก็ได้ที่คนในกลุ่มตกลงกัน ผู้เล่นควรจะรู้สึกปลอดภัยในการพูด “หยุด” และหยุดเกมจนกว่าปัญหาจะคลี่คลาย ผู้ที่เป็นคนให้สัญญาณจะเป็นคนบอกว่าอยากให้ปรับเปลี่ยนอะไร แต่ไม่ต้องอธิบายว่าทำไม สัญญาณจะไม่ทำให้เกิดการซักถามหรือโต้แย้งใด ๆ ต้องขอบคุณผู้เล่นที่ซื่อสัตย์ต่อความต้องการของพวกเขา ปรับเรื่องให้เป็นไปตามนั้นและดำเนินเกมต่อไป

ควรแจ้งให้ผู้เล่นทราบว่าถ้าใครรู้สึกไม่สบายใจที่จะใช้สัญญาณ พวกเขาสามารถลุกออกจากเกมหรือขอพักได้เพื่อที่จะคุยกับคุณแบบส่วนตัว ผู้เล่นอาจจะให้อำนาจผู้เล่นอื่นในการส่งสัญญาณแทน เป็นหน้าที่ของ DM ที่จะคอยสังเกตความต้องการของผู้เล่นอย่างจริงจัง และใช้เครื่องมือที่คุณมีในการปรับเกมให้เหมาะสม

ความขัดแย้งภายในคณะผจญภัย

เมื่อมีความขัดแย้งเกิดขึ้นระหว่างตัวละครในคณะผจญภัย มันมักจะมีสัญญาณหนึ่งในสามอย่างนี้เกิดขึ้น:

ผู้เล่นที่ชอบขัดขวางคนอื่น ผู้เล่นคนหนึ่งจะแสดงออกว่าต่อต้านสังคมในเกม การตอบสนองต่อผู้เล่นแบบนี้มีแนะนำใน “พฤติกรรมต่อต้านสังคม”

ความขัดแย้งของผู้เล่น ความขัดแย้งระหว่างตัวละครบางครั้งเป็นการแสดงออกว่าผู้เล่นมีความขัดแย้งกัน ความขัดแย้งแบบนี้ควรต้องจัดการนอกเกม พยายามให้ผู้เล่นแก้ไขข้อขัดแย้งกันนอกเกม ถ้าความขัดแย้งยังเกิดขึ้นในเกมอยู่เรื่อย ๆ คุณอาจต้องขอให้พวกเขาออกจากเกมไปสักระยะหรือเลิกเล่นกันไปเลย

การสวมบทบาท ความขัดแย้งระหว่างตัวละครอาจจะไม่เป็นเรื่องแย่เสมอไป มันไม่เป็นไรเลยถ้าตัวละคร (และผู้เล่น) จะเห็นต่างกันเกี่ยวกับการจัดการศัตรูที่จับมาได้ หรือควรจะเข้าข้างไหนในการแข่งกินเบียร์ แต่ถ้าความเห็นต่างเริ่มจะร้อนแรงขึ้น ให้หยุดพักและพูดคุยกัน นอกบทบาท ว่าผู้เล่นอยากให้ดำเนินเกมไปทางไหนดี

ถ้าคุณไม่สามารถบอกได้ว่าความขัดแย้งนี้เป็นเรื่องของบทบาทในเกมหรืออย่างอื่น ให้พูดคุยกับผู้เล่นก่อน

เคารพผู้เล่น

ผู้เล่นของคุณต้องรู้ตั้งแต่เริ่มเล่นว่าคุณจะรันเกมที่สนุก, ยุติธรรม, และออกแบบมาเพื่อพวกเขาโดยเฉพาะ ที่คุณจะอนุญาตให้แต่ละคนมีส่วนร่วมกับเรื่องราว และคุณจะให้ความสนใจกับพวกเขาเมื่อถึงตาเล่น ผู้เล่นของคุณจะเชื่อใจคุณว่าอันตรายจากการผจญภัยจะไม่พุ่งเป้ามาที่คนใดคนหนึ่งเพราะเรื่องส่วนตัว อย่าได้ทำให้ผู้เล่นรู้สึกไม่สบายใจและรู้สึกว่าตนเองตกเป็นเป้าทำร้ายเด็ดขาด

คุณทำแบบนั้นจริง ๆ เหรอ?

ผู้เล่นสามารถเปลี่ยนสิ่งที่ตัวละครเขาทำได้หรือไม่? DM บางคนจะกำหนดเส้นตายไว้เลยว่า: “ถ้าคุณพูดออกมา แสดงว่าตัวละครของคุณทำมันตามนั้น” เป็นจุดยืนที่มักจะทำให้ผู้เล่นระมัดระวังคำพูดอย่างมาก ซึ่งอาจทำให้เกิดบรรยากาศจริงจังและไม่ตลก

DM บางคนจะให้ผู้เล่นเปลี่ยนใจได้อย่างอิสระ สิ่งนี้ทำให้เกิดเกมที่ผ่อนคลาย ซึ่งอาจจะทำให้เกมดำเนินไปช้าบ้าง

การประณีประนอมส่วนใหญ่คือการใช้กฏที่ว่าผู้เล่นสามารถเปลี่ยนใจหรือเปลี่ยนสิ่งที่ตัวละครทำจนถึงจุดที่พวกเขาได้รับผลจากการกระทำนั้น เมื่อคุณบรรยายว่าผลลัพท์เกิดอะไรขึ้นไปแล้ว มันจะสายไปที่ผู้เล่นจะเปลี่ยนใจ

กระจายแสงให้ทุกคน

เมื่อเป็น DM อย่ามีลูกรักลูกชัง อย่าให้ผู้เล่นคนหนึ่งเป็นคนพูดตลอดเวลา และตต้องแน่ใจว่าคุณได้ให้โอกาสตัวละครทุกตัวได้ทำสิ่งต่าง ๆ โดยเฉพาะในช่วงการสำรวจและปฏิสัมพันธ์ทางสังคม แทนที่จะเน้นไปที่ผู้เล่นคนเดียว

บางครั้งคุณอาจจะเจอกับผู้เล่นที่ชอบบอกให้คนอื่นทำนั่นทำนี่ ยึดเอาไอเท็มเวทย์มนต์ที่ดีที่สุดไปเป็นของตัวเอง บุลลี่ผู้เล่นคนอื่น และไม่ยอมให้คนอื่นมีแสง เมื่ออยู่นอกเกม ให้พูดคุยตรง ๆ ชี้ให้เห็นว่ามันทำให้เกมไม่สนุก และขอให้เขาลดพฤติกรรมลง ถ้าไม่ยอมเปลี่ยนก็อาจจะเล่นด้วยกันต่อไม่ได้

ปัญหาบางอย่างเกิดขึ้นเมื่อผู้เล่นคิดว่าสไตล์การเล่นของตัวเองนั้นเจ๋งกว่าคนอื่น และพวกเขาหมดความอดทนกับเนื้อเรื่องที่ออกแบบสำหรับตัวละครอื่น ให้ย้ำกับผู้เล่นคนนั้นว่าคุณต้องดูแลคนทั้งโต๊ะ ไม่ใช่แค่ผู้เล่นคนเดียว

ขอบเขตของเรื่องเศร้า

ผู้เล่นบางคนไม่อยากร่วมลงทุนในโลกของเกมเพราะพวกเขาไม่อยากเห็นผู้คนและสถานที่พวกเขารักถูกทำร้ายหรือทำลายไป ผู้เล่นบางคนมีเรื่องราวภูมิหลังที่เต็มไปด้วย NPC ที่เขารัก และคาดหวังอย่างมากกว่า DM จะเลือกคนเหล่านั้นมาใช้เป็นเหยื่อ, เป็นผู้เคราะห์ร้าย, และเป็นตัวร้ายที่คาดไม่ถึง มันสำคัญมากที่จะเข้าใจสิ่งที่ผู้เล่นคาดหวังเพื่อที่คุณจะไม่ปล่อยให้เขาเคว้งคว้างเพราะไปทำลายสิ่งที่พวกเขารัก หรือทำให้น่าเบื่อเพราะไม่หยิบอะไรจากภูมิหลังตัวละครมาใช้เลย

เมื่อคุณให้ตัวร้ายคุกคามผู้คนและสถานที่ที่ตัวละครรัก ให้แน่ใจว่าตัวละครมีโอกาสที่จะขัดขวางผลลัพท์ที่เลวร้ายนั้น ระหว่างเกม ตัวละครควรมีโอกาสที่จะหลีกเลี่ยงหรือจำกัดความเสียหายในวิธีแบบฮีโร่ เรื่องเศร้าควรเป็นผลสืบเนื่องจากการกระทำและการตัดสินใจของตัวละครไม่ใช่เรื่องที่ถูกกำหนดไว้แล้ว ช่วงเวลาที่แก้ไขอะไรไม่ได้ในการเผชิญหน้ากับโศกนาฏกรรมนั้นน่าจะเหมาะกับการเป็นเรื่องราวภูมิหลังของตัวละครมากกว่า

การทอยลูกเต๋าของ DM

คุณควรจะซ่อนการทอยลูกเต๋าหลังฉาก DMS หรือคุณควรจะทอยแบบเปิดให้ทุกคนเห็น? เลือกทางใดทางหนึ่งและใช้มันตลอดการเล่น แต่ละแบบมีอธิบายด้านล่าง:

ทอยลูกเต๋าแบบซ่อน การซ่อนการทอยทำให้มันดูลึกลับและให้โอกาสคุณในการปรับเปลี่ยนผลได้ถ้าคุณต้องการ ตัวอย่างเช่น คุณสามารถข้ามการทอยได้คริติคัลเพื่อรักษาชีวิตของตัวละคร อย่าปรับเปลี่ยนค่าการทอยบ่อยนักแม้ว่าผู้เล่นจะไม่รู้ว่าเมื่อไรที่คุณทอยหลอกพวกเขาก็ตาม (fudge การทอยฟัดจ์)

ทอยแบบเปิดเผย การทอยในที่เปิดจะแสดงให้เห็นว่าคุณไม่ได้เลือกปฏิบัติ คุณไม่ได้ทอยหลอกเพื่อประโยชน์หรือผลเสียต่อตัวละคร

แม้ว่าโดยปกติคุณจะทอยหลังฉาก มันก็สนุกดีที่จะทอยแบบพิเศษให้ทุกคนตื่นเต้นไปกับผลของมัน

ผู้เล่นที่ระมัดระวังเกินไป

ผู้เล่นที่ระมัดระวังเกินไปสามารถทำให้เกมช้าลงโดยการตรวจสอบหินทุกก้อน, ประตู, และกำแพงในดันเจียนเพื่อหากับดักและอันตรายที่ซ่อนอยู่ บางครั้งพฤติกรรมนี้เกิดจากการผจญภัยครั้งก่อนที่เต็มไปด้วยความประหลาดใจที่ทำให้เกิดประสบการณ์แย่ ๆ และบางครั้งก็เป็นเพราะบุคลิกของตัวผู้เล่นเองด้วย

นี่เป็นเทคนิคบางส่วนที่คุณสามารถนำไปใช้ในเกมเพื่อส่งเสริมให้ผู้เล่นกล้าหาญมากขึ้น:

หลีกเลี่ยงอันตรายแบบสุ่ม ให้หลีกเลี่ยงกับดักและการซุ่มโจมตีที่ให้ความรู้สึกแบบสุ่มและไม่ได้มีความสำคัญอะไรกับการผจญภัยโดยรวม

สร้างแรงกดดันจากเวลา สร้างสถานการณ์ที่ตัวละครต้องไปถึงจุดหมายหรือทำเป้าหมายให้สำเร็จโดยมีเวลาจำกัด (ใช้เทคนิคนี้อย่างระมัดระวัง เพราะเวลาจำกัดอาจจะทำให้ผู้เล่นวิตกกังวลมากขึ้น)

การเผชิญหน้าที่ได้รับแจ้งก่อน (* Telegraph Encounters). ให้ผู้เล่นได้รู้ถึงคำเตือนว่าจะมีการเผชิญหน้าที่เลี่ยงไม่ได้ พวกเขาอาจจะได้ยินเสียงฝีเท้ายักษ์ที่หนักจนพื้นสะเทือนหรือเห็นมังกรบินผ่านหัวไปก่อนที่พวกเขาจะได้เจอมัน สิ่งนี้จะสนับสนุนให้ผู้เล่นของคุณมุ่งไปข้างหน้าหรือหลบเลี่ยงการเผชิญหน้าไปมากกว่าจะกังวลเกี่ยวกับการถูกซุ่มโจมตี

* Telegraph หรือโทรเลข เป็นการส่งข้อความสั้นผ่านสายไฟฟ้า เมื่อก่อนต้องไปส่งที่ที่ทำการไปรษณีย์ซึ่งจะมีเครื่องส่งและปลายทางจะมีเครื่องรับ ในไทยเลิกใช้ไปเมื่อ 30 เมษายน พ.ศ. 2551 ดูเพิ่มเติม: โทรเลข

ในบริบทนี้คือคือการส่งข้อความมาบอกก่อนว่าจะมีการเผชิญหน้านะ ไปเจอได้เลยไม่ต้องห่วงกับดักแถวนี้

ถ้าเทคนิคในเกมแบบนี้ไม่ให้ผลที่ต้องการ ให้คุยกันนอกเกมกับผู้เล่นเกี่ยวกับสิ่งที่ทำให้พวกเขาเล่นกันอย่างระมัดระวัง ตกลงกันโดยจะไม่มีสิ่งเหล่านั้นเกิดขึ้นในเกมของคุณ ซึ่งจะทำให้เกมดำเนินไปได้ลื่นไหลมากขึ้น

เคารพ DM

เมื่อเป็น DM คุณมีสิทธิที่จะคาดหวังว่าผู้เล่นของคุณจะเคารพคุณและความพยายามของคุณที่จะทำให้เกมสนุกสำหรับทุกคน ผู้เล่นต้องให้คุณเป็นผู้นำแคมเปญ (โดยมีพวกเขาเป็นผู้ให้ข้อมูลและตัดสินใจ), ตัดสินใจใช้กฏ, และตัดสินความขัดแย้ง และเมื่อคุณบรรยายกิจกรรมในเกม ผู้เล่นควรจะให้ความใส่ใจ

การทอยลูกเต๋าของผู้เล่น

ผู้เล่นควรทอยลูกเต๋าแบบเปิดเผยให้ทุกคนเห็น ถ้าผู้เล่นหยิบลูกเต๋าก่อนที่คนอื่นจะเห็นว่าทอยได้อะไร พยายามบอกให้ผู้เล่นอย่าปิดเป็นความลับ

เมื่อลูกเต๋าหล่นพื้น คุณจะนับค่านั้นหรือให้ทอยใหม่? ถ้ามันกลิ้งไปพิงกับหนังสือ คุณจะยกหนังสือออกและใช้ค่านั้นหรือจะให้ทอยใหม่? ให้พูดคุยกับผู้เล่นเกี่ยวกับคำถามเหล่านี้และบันทึกคำตอบไว้เป็นกฏเฉพาะโต๊ะ (house rules)

สัญญาทางสังคมของการผจญภัย

คุณต้องให้เหตุผลที่สมเหตุสมผลและน่าสนใจกับตัวละครเพื่อให้พวกเขาออกผจญภัยไปตามที่คุณเตรียมมา (ดู “การเชิญชวนผู้เล่น” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide) สำหรับคำแนะนำในหัวข้อนี้) และเพื่อให้เท่าเทียมกัน ผู้เล่นควรจะตามน้ำไปกับเงื่อนไขการผจญภัยเหล่านั้นด้วย เป็นเรื่องธรรมดาที่ผู้เล่นของคุณจะถามกลับมากว่าทำไมตัวละครของพวกเขาถึงต้องทำสิ่งที่คุณขอให้พวกเขาทำด้วย แต่มันจะเป็นสิ่งไม่ควรถ้าพวกเขาจะไม่สนใจสิ่งที่คุณเตรียมมาและพยายามทำตามใจไปในทิศทางอื่น

ถ้าคุณรู้สึกว่ามีแต่คุณที่ต้องปรับเปลี่ยนอะไรหลายอย่างแต่ผู้เล่นไม่ได้ปรับอะไรเลย ให้ลองพูดคุยกันนอกเกม พยายามทำความเข้าใจถึงเงื่อนไขการผจญภัยที่ตัวละครของพวกเขาอยากทำ และทำให้แน่ใจว่าผู้เล่นของคุณเข้าใจสิ่งที่คุณพยายามเตรียมการผจญภัยเพื่อพวกเขา

การถกเถียงกันในเรื่องของกฏ

ให้สร้างนโยบายเกี่ยวกับการถกเถียงกันเรื่องกฏเมื่อเล่นเกม บางกลุ่มไม่คิดอะไรหากจะหยุดเกมไว้ก่อนเพื่อที่จะปรึกษากันเกี่ยวกับการตีความกฏ บางกลุ่มเลือกที่จะให้ DM เป็นคนตัดสินและเล่นต่อไป ถ้าคุณประสบกับปัญหาในการใช้กฏในการเล่น ให้บันทึกมันไว้ก่อนและกลับมาศึกษากันอีกทีในภายหลัง

ผู้เล่นบางคนชอบที่จะใช้กฏมาค้านการตัดสินใจของคุณ ขณะที่ผู้เล่นแบบนั้นสามารถเป็นผู้ช่วยเหลือได้เมื่อคุณติดขัดหรือคุณใช้กฏผิดไป แต่ผุ้เล่นที่ค้านบ่อยเกินไปก็ทำให้เกมหยุดชะงักได้เหมือนกัน

ถ้าผู้เล่นต้องการหยุดเกมไว้ก่อนเพื่อค้นหากฏหรืออ้างอิงเฉพาะ คุณสามารถให้ผู้เล่นนั้นใช้เวลาค้นหาได้โดยคุณและผู้เล่นอื่นก็เล่นกันต่อไป ตัวละครของผู้เล่นนั้นจะออกจากเกมไปชั่วคราวจนกว่าผู้เล่นจะกลับมา มอนสเตอร์จะไม่โจมตีตัวละครนั้น และตัวละครจะใช้แอ็คชัน หลบหลีก (Dodge) ในการต่อสู้จนกว่าผู้เล่นจะกลับมา วิธีการนี้จะทำให้เกมยังดำเนินต่อไปได้โดยไม่ถูกหยุดโดยผู้เล่นคนเดียว

สิ่งที่ตัวละครรู้

ส่งเสริมให้ผู้เล่นเล่นเป็นตัวละครของพวกเขาภายในภาวะที่ตัวละครมีความรู้ความเข้าใจในสถานการณ์อย่างจำกัด มันจะช่วยได้มากถ้ารักษาขอบเขตของสิ่งที่ตัวละครรู้และสิ่งที่ผู้เล่นรู้ ทำได้ง่าย ๆ โดยถามผู้เล่นว่า “ตัวละครของคุณคิดอะไรอยู่?”

การนำความคิดสมัยใหม่ไปใช้ในเกมเป็นหนึ่งในสิ่งที่มักผิดพลาดในการเล่น คุณอาจจะต้องคอยย้ำผู้เล่นว่าตัวละครจะไม่มีความรู้ในการทำสิ่งใด ๆ ที่ไม่มีอยู่ในโลกของเกม เช่นปืนสมัยใหม่หรือยาปฏิชีวนะ และพวกเขาไม่มีความรู้ทางวิทยาศาสตร์สมัยใหม่แบบที่ผู้เล่นรู้ (ซึ่งก็ไม่สามารถใช้ได้ในจักรวาลของเกมเช่นกัน)

เช่นเดียวกัน บางครั้งผู้เล่นก็คุ้นเคยกับการผจญภัยที่พิมพ์ขายที่คุณกำลังรันอยู่ หรือรู้ข้อมูลใน คู่มือมอนสเตอร์ ไม่มากก็น้อย พยายามให้ผู้เล่นแยกสิ่งที่พวกเขารู้จากสิ่งที่ตัวละครรู้ และให้ผู้เล่นคนอื่นได้ค้นพบความรู้นั้นโดยการเล่นตามเกมไป

พฤติกรรมต่อต้านสังคม

บางคนเล่น D&D เพราะมันให้พวกเขาได้ทำสิ่งที่ไม่สามารถทำได้ในชีวิตจริงผ่านทางตัวละคร เช่นต่อสู้กับมอนสเตอร์, ร่ายคาถา ฯลฯ อย่างไรก็ตามสำหรับบางคนนั้น นี่หมายถึงการอาละวาดในเมืองหรือทรยศเพื่อนในวิธีต่าง ๆ สิ่งที่พวกเขาต้องการไม่ใช่การผจญภัยอย่างวีรบุรุษ แต่เป็นการใช้กฏเกมเพื่อสนองจินตนาการต่อต้านสังคม

ถ้าพฤติกรรมนี้เกิดขึ้นในเกมของคุณ มันน่าจะเป็นเวลาของการเปิดการพูดคุยเกี่ยวกับเกมที่คุณต้องการเล่น ถ้าเป็นแค่ผู้เล่นคนเดียวที่ก่อปัญหา ก็จะเป็นเวลาที่เหมาะเจาะในการประกาศ: ผู้เล่นที่ควบคุมตัวเองไม่ได้ที่ยังต้องการเล่นกับกลุ่มต่อไป ต้องหยุดพฤติกรรมที่ขัดขวางคนอื่นและกลับมาเป็นส่วนหนึ่งของทีม อย่าปล่อยให้ผู้เล่นลอยนวลไปสร้างความรำคาญให้คนอื่นเพียงเพราะจะอ้างว่า “ก็ตัวละครของฉันจะทำแบบนี้อ่ะ”

ตัวละครแบบชั่วร้าย ผู้เล่นที่ต้องการเล่นเป็นตัวละครตัวร้ายอาจจะพยายามหาวิธีที่จะทำพฤติกรรมต่อต้านสังคมในเกม ถ้าผู้เล่นขออนุญาตเล่นตัวละครชั่วร้ายหรือมาเล่นพร้อมตัวละครที่สร้างไว้แล้ว ให้พูดคุยกับผู้เล่นเกี่ยวกับสิ่งที่เขาคิดไว้และให้แน่ใจว่าแผนการนั้นเข้ากับความคาดหวังของกลุ่ม บางครั้งผู้เล่นต้องการที่จะสำรวจการเล่นตัวละครชั่วร้ายโดยมีเหตุผลที่ดี (และไม่ขัดขวางการเล่นของคนอื่น) และบางครั้งทั้งกลุ่มก็ตัดสินใจว่ามันน่าจะสนุกดีถ้าเล่นตัวละครชั่วร้ายกันทั้งกลุ่ม นี่เป็นตัวเลือกที่ดีโดยที่ทุกคนเห็นพ้องกันว่าแคมเปญจะไปทางนั้น

ผู้เล่นใช้กฏในการสร้างความได้เปรียบ

ผู้เล่นบางคนชอบที่จะขุดลึกลงไปในกฏทุกกฏของ D&D เพื่อมองหาการผสมผสานที่ให้ผลสุดยอดที่สุด การปรับแต่งนี้เป็นส่วนหนึ่งของเกม (ดู “รู้จักผู้เล่นของคุณ” ใน คู่มือดันเจียนมาสเตอร์ (Dungeon Master’s Guide)) แต่บางครั้งก็อาจจะข้ามเส้นไปจนเป็นการเอารัดเอาเปรียบและทำให้คนอื่นหมดสนุก

การตั้งความคาดหวังที่ชัดเจนจะเป็นส่วนสำคัญเมื่อต้องเจอกับการฉกฉวยผลประโยชน์จากการใช้กฏนี้ ให้จำหลักการนี้ไว้:

กฏเกมไม่ใช่กฏฟิสิกส์ กฏของเกมมีเป้าหมายในการให้ประสบการณ์การเล่นเกมที่สนุก ไม่ได้เป็นการอธิบายกฏทางฟิสิกส์ในโลกของ D&D อย่าเอากฏของโลกจริงมาใช้ อย่าให้ผู้เล่นอ้างว่าคนธรรมดาตั้งแถวส่งของต่อกันสามารถเร่งความเร็วหอกให้เร็วเท่าความเร็วแสงได้ โดยการใช้แอ็คชัน เตรียมพร้อม (Ready) และส่งต่อหอกให้คนข้างหน้า แอ็คชันเตรียมพร้อมนั้นมีไวสำหรับทำแอ็คชันแบบฮีโร่ มันไม่ได้เป็นตัวกำหนดขอบเขตทางฟิสิกส์ที่ควรจะเกิดได้ภายในเวลา 6 วินาทีของรอบการต่อสู้

เกมไม่ได้เป็นระบบเศรษฐกิจ กฏของเกมไม่ได้ตั้งใจให้เป็นแบบจำลองทางเศรษฐศาสตร์จริงจัง และผู้เล่นที่มองหาช่องโหว่ที่จะสร้างความมั่งคั่งไร้ขีดจำกัดโดยใช้คาถาผสมกันเป็นการเอารัดเอาเปรียบโดยใช้กฏ

การต่อสู้มีไว้สำหรับศัตรูเท่านั้น กฏบางอย่างจะใช้กับการต่อสู้เท่านั้น หรือในขณะที่ตัวละครทำสิ่งต่าง ๆ ในลำดับการต่อสู้ อย่าให้ผู้เล่นโจมตีกันเองหรือสิ่งมีชีวิตที่ไร้ทางสู้เพื่อเปิดใช้กฏนี้

การตีความกฏจะอิงอยู่กับความดีงาม กฏจะถือว่าทุกคนอ่านและตีความกฏโดยสนใจที่ความสนุกของกลุ่มอย่างจริงใจและใช้กฏเพื่อสิ่งนั้น

การบอกกล่าวถึงหลักการนี้ก่อนเล่นจะช่วยป้องกันผู้เล่นที่ชอบใช้ช่องโหว่ไม่ให้พยายามทำสิ่งนั้น ถ้าผู้เล่นยังพยายามจะบิดเบือนกฏ ให้พูดคุยกันนอกเกมและขอให้หยุด

ความรู้ในกฏเกม

คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องเป็นผู้เชี่ยวชาญในกฏถึงจะเป็น DM ได้ แน่นอนที่มันจะช่วยได้มากถ้าคุณคุ้นเคยกับกฏ แต่การสร้างความสนุกนั้นสำคัญกว่าการบังคับใช้กฏอย่างสมบูรณ์ ถ้าคุณไม่แน่ใจว่าจะใช้กฏอย่างไรในสถานการณ์ที่พบเจอ คุณสามารถถามความเห็นของผู้เล่นทั้งหมดได้ มันอาจจะใช้เวลาบ้าง แต่มันก็เป็นเรื่องที่เป็นไปได้ที่คุณจะได้คำตอบที่เป็นธรรมกับทุกคน และนั่นเป็นสิ่งที่สำคัญมากกว่าคำตอบที่ “ถูกต้อง”

คุณไม่จำเป็นต้องรู้ทุกคาถาหรือคุณสมบัติของทุกคลาส ตั้งความคาดหวังไว้ได้ว่าผู้เล่นทุกคนจะรับผิดชอบในการบอกคุณว่าความสามารถและคาถาของพวกเขาทำอะไรได้บ้าง

กฏสำหรับการเล่นออนไลน์

การตั้งความคาดหวังก็สำคัญกับการเล่นออนไลน์ไม่ต่างจากการเล่นบนโต๊ะ

กลุ่มบางกลุ่มจำกัดการเล่าเรื่องตลกที่ไม่เกี่ยวกับตัวละคร ความคิดเห็น และมีมให้อยู่ในช่องข้อความ เพื่อให้ช่องเสียงเน้นไปที่เกม แต่บางกลุ่มอาจพบว่าการสนทนาแยกกันเป็นข้อความในขณะที่เกมดำเนินไปนั้นรบกวนสมาธิ เลือกตัวเลือกที่เหมาะกับกลุ่มของคุณที่สุด

ใครจะเป็นคนเลื่อนโทเคนในโปรแกรมโต๊ะเสมือน? ผู้เล่นคาดว่าจะใช้การทอยลูกเต๋าจากระบบที่มีอยู่หรือไม่? หรือมันก็ใช้ได้ถ้าจะทอยลูกเต๋าจริงและบอกผล? เทคโนโลยีที่คุณใช้จะเป็นตัวกำหนดคำตอบของคำถามเหล่านี้ หรืออาจจะสร้างคำถามเพิ่มเติมเมื่อคุณต้องจัดการเล่นจริง